Terminalia Festival Walk 2025

Shetland 24th February 2025

The annual Festival of Terminalia takes place on and around 23rd February. https://terminaliafestival.org/

Terminalia was an ancient Roman festival in honour of the god Terminus, who presided over boundaries. His statue was a stone or post stuck in the ground to distinguish between properties. Terminalia was traditionally celebrated on the last day of the old Roman year, which was February.

Places are defined by borders and boundaries, what's there and what isn't. The current Festival of Terminalia is about celebrating these boundaries and borders - real, historical, symbolic, imagined; places of beginnings, endings, and thresholds. Its theme this year is ‘hope’

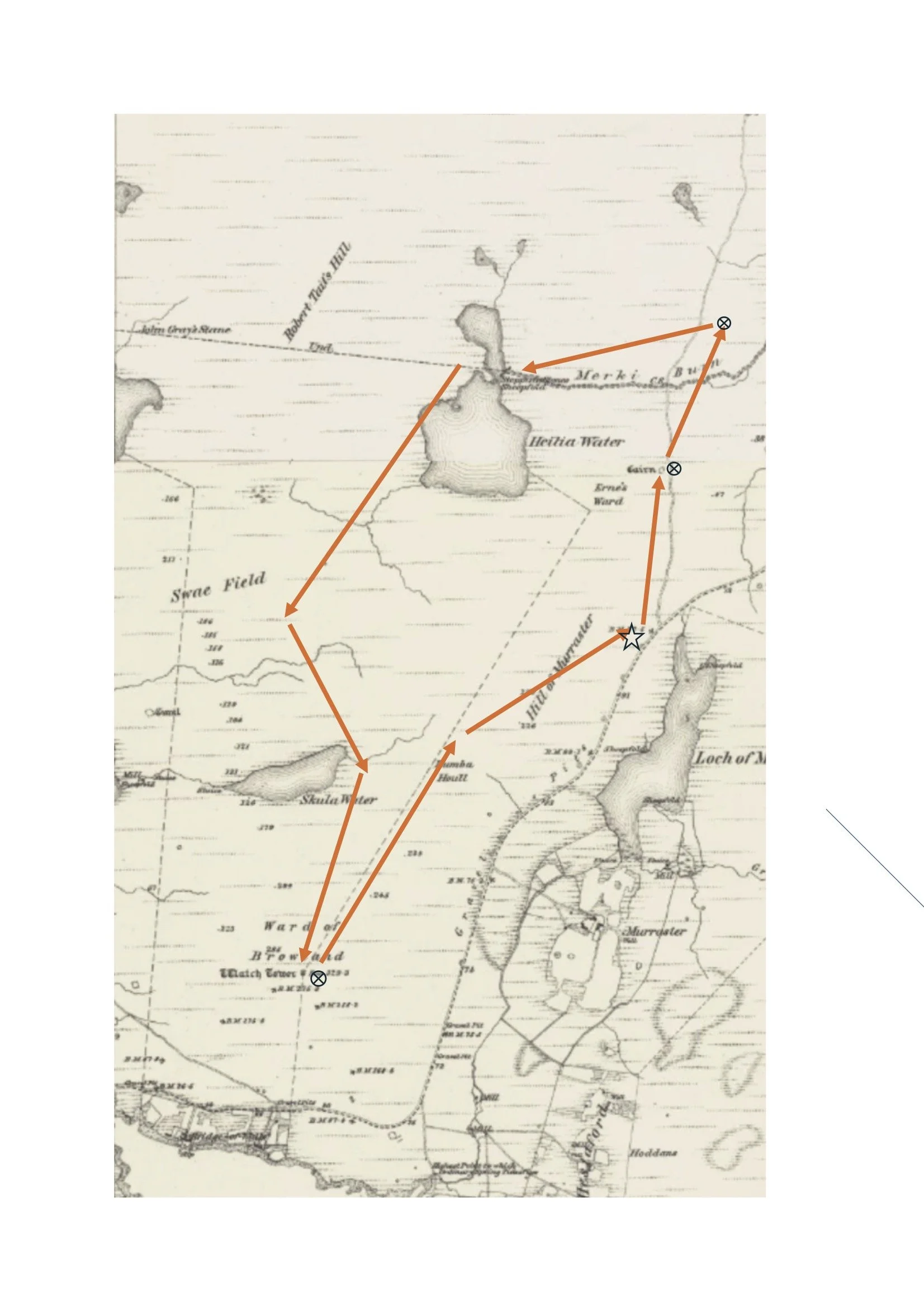

Our Terminalia walk imagined and conjured a processional route connecting three prehistoric burial cairns on Shetland’s West Side, as indicated on either the OS 6 inch first edition map of 1878 or the modern 1:2500. As we walked we thought about this year’s terminalia theme, hope, considered the term’s transhistorical meanings, the temporal distance between ourselves and the people laid to rest in the great stone tombs we encountered, and the points of cognitive convergence that we might share with them across the centuries.

1878 first edition map showing our route and cairns. The star shows our starting and end points, the X in a circle shows the position of the cairns

The wind’s blowing but the sun is shining, bringing hope to our hearts, as we meet at the carpark on the West Burrafirth road. Our intrepid party of five sets off for a short distance up the road, veering off to scale a ditch and fence (the first of many to overcome), to make our way up to the first of our chambered cairns.

Photo credit: Janette Kerr - West Burrafirth Road

Lying partway up the hillside, there’s not much of it left intact – a lot of scattered stones - but it’s still possible to make out the curved heel-shape that describes it. We pace around the monument discussing the structure and scale.

Jim: It’s a revelation to see the size of this first one and the clear evidence of chambers extending right to the edge of what remains. So much so, I am convinced it’s more like a house than a burial cairn! But I am no archaeologist, the main thing is how real it is to me - leaping out of the heather on the side of an unremarkable hillside. But so tantalizingly enigmatic!

Photo credit: Janette Kerr - Ernes Ward, chambered cairn

It’s true that Neolithic houses and Neolithic tombs were constructed to a similar pattern, and although this one has been inspected by archaeologists and declared a chambered burial cairn c.3500 BC, there’s been no thorough excavation to date and the interior shape seems not to have been recorded. We try to work out where the entrance was. Most have a low central passage with niches lying either side, but it’s hard to be sure here.

Steve: The idea that neolithic builders in stone came up with two very similar design ideas, one for the use of the living and the other for the use of the dead, surely has something to tell us about ancient perceptions of the self…

We wonder if it may have been both domestic dwelling and resting place for the dead; people keeping the bones of their ancestors close, perhaps burying them in the floor. We know that burial practices were not always consistent. In other parts of the UK, bodies were sometimes buried whole, but the chambers in these Shetland cairns were too small for that. Where bones have been recovered by excavation they’re not complete skeletons; bodies seem to have been dismembered. But how did that come about? Might the dead have been burnt or perhaps left at first for birds and other animals to pick at so that their bodies were incomplete when finally interred?.

Photo credit Janette Kerr - Ernes Ward chambered cairn

Our reading tells us that bones were moved around, even removed and replaced according to custom, and through this interaction between the living and the dead, the deceased retained a presence and a place in their community. These were collective places of burial, not tombs for revered single individuals. The practice of permanently burying individuals intact, in their own graves, emerged only at the end of the Neolithic period, representing a shift in thinking that saw the grave as the point at which the deceased became removed from society, both in place and in time.

(https://whiteadder.aocarchaeology.com/archaeology/neolithic-bronze-age-markers-in-the-landscape/)

Jim: The questions rush in… How has the ground level changed with peat deposition? How much better was the climate? When was the tree cover exhausted? How much of these earlier inhabitants’ houses have been covered by rising sea levels? How hard was life? How strong were they? Did they have time to sit around the fire and have a sing song?

Leaving this site, we make our way back to the road to find our second cairn on the other side of the Merki Burn (HU279535).

Sited part way up a short rise, even less of this one remains. It’s another tumble of stones lying amongst the heather, but it’s just possible to make out a rough outline and imagine how much ground it once covered.

Photo credit: Steve Poole, Ernie’s Field, cairn no 2

This one is round, rather than heel-shaped and probably never chambered, so entrance would have been through the roof to a cist or pit within. Some archaeologists suggest these simpler tombs belong not to the neolithic but to the later bronze age. We wonder what persuaded the builders to abandon what seems to us the more sophisticated design of the earlier (and larger) chambered cairns and make these instead. Does it indicate a changing relationship with death itself? But other archaeologists think the two designs probably co-existed, so we get no further with that.

Photo credits: Jim Sutherland and Susan Pearson - stones amongst the cairn

Noticing several holes in the ground I put my hand into them, and am surprised to discover that my whole arm goes down - the stones are considerable in size - they go down a long way, feel smoothed as though shaped. Again, it would be great to have it properly excavated. We stare back up towards our first cairn and wonder about the relationship between the two sites - as terminal monuments to the life-giving waters of the burn dividing them. Was the burn there when they were constructed? Why were they both placed here and why not built at the top of the hills? Maybe the archaeologists have got it wrong and one was a homestead and the other a burial place? Much to ponder.

We try to imagine the process of entering and leaving the cairns when they were still functioning. The entrance passages were very low so the only way in would have been on hands and knees. Orkney burial chambers had much the same access system but much larger interiors and this gets us wondering whether the passage and interior chamber were intended to represent birth canal and womb, the beginning and ending of life.

Susan: If we think about the landscape as body, or life giver, with a cairn’s small entrance opening into larger structure as a metaphor for the womb…. about embodied landscapes, and the possibility that there is little separation between nature, land and human bodies, with the life/death/rebirth cycles of body and environment inseparable and entangled.

Looking around I think about the surrounding landscape populated by neolithic people, and how they interacted with it. What was it about this particular location that led them to chose it to place the remains of their loved ones ? It would not have been chosen randomly, but probably close to where they lived, perhaps so they could have looked up to see them. How often did they visit them? Not far from here I can see down to the Vadills, a complex lagoon system at the head of the Brindister Voe (now a special conservation site and sometimes used by fishermen), and across to the far hills on the east side of Shetland.

Photo credit: Jim Sutherland - following the Merki Burn

Back to the road, we climb another fence and follow a rather well laid-out track to reach the edges of Heilia Water. A pause for refreshments; those of us with sketchbooks draw, Steve climbs the hill in search of moss sporophytes to photograph.

Photo credit: Steve Poole, Heilia Water

Photo credit: Steve Poole, Heilia Water

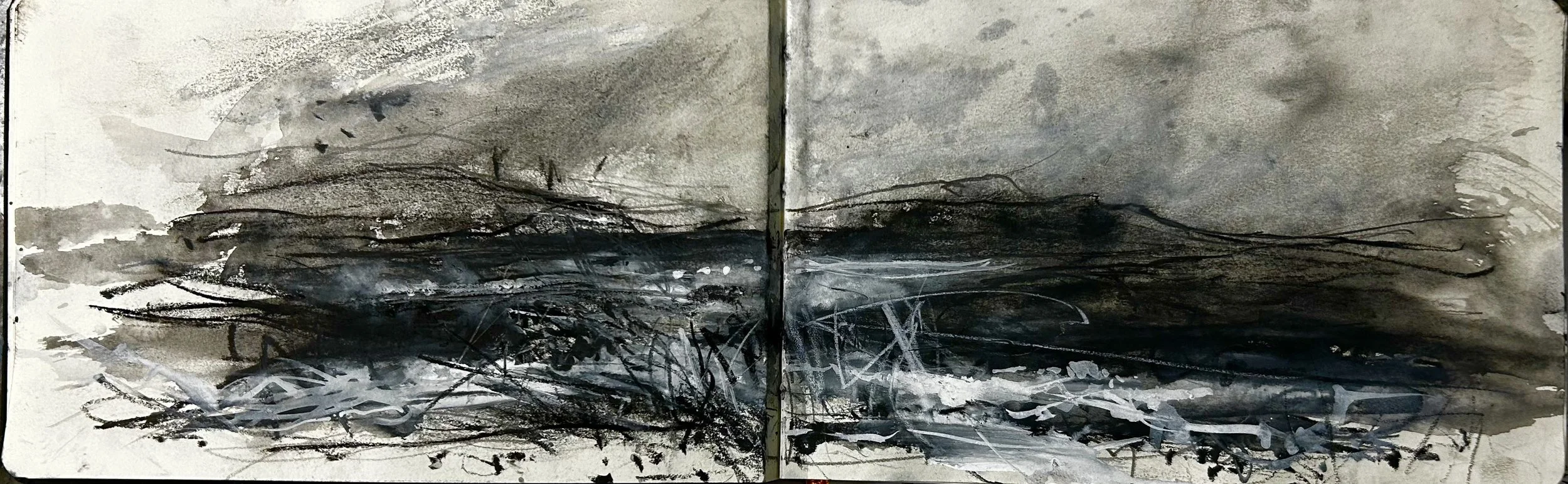

Janette Kerr, plein air sketch - Heilia Water

Janette Kerr, plein air sketch - Heilia Water

Janette Kerr, plein air sketch - Heilia Water

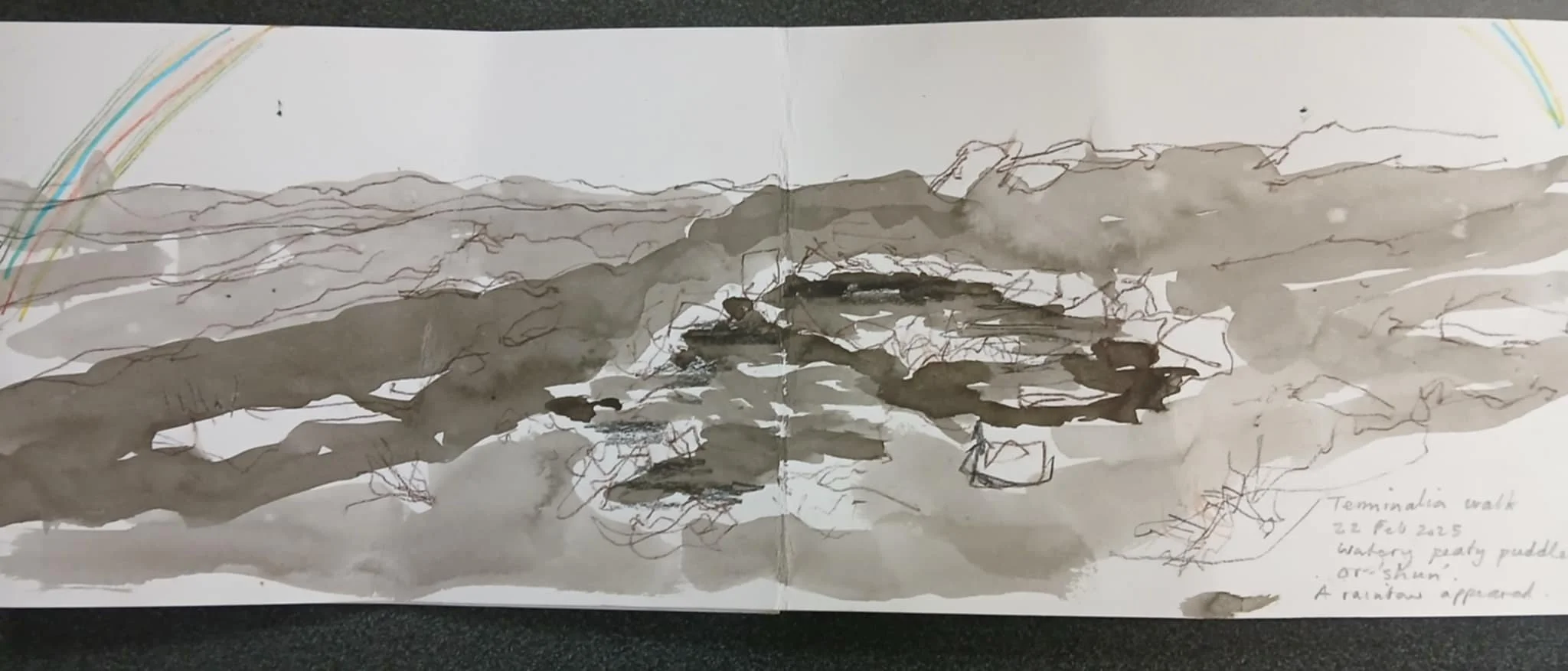

Susan Pearson, plein-air sketch - Heilia Water

Susan Pearson, 3 plein-air sketches - Heilia Water island, and wall

Susan Pearson, Plein-air sketches - Heilia Water island

Photo credit: Steve Poole, Sporophyte

The old map marks a sheepfold and a rather handy line of stepping stones crossing the loch and fortunately they’re still there – in the form of a pile of variously shaped rocks (I wouldn’t have called them stones). By various means and with a bit of encouragement, we all manage to scramble across, saving ourselves a longer walk around the loch.

Photo credit: Susan Pearson - Crossing the stepping stones, Heilia Water

The ground is covered in thick heather which, Susan remarks, makes walking and looking at the landscape at the same time rather challenging. A steep climb up and we stand on a hilltop called Swae Field; a modern marker cairn is indicated on the new map, but no ancient burial cairns. Yet three separate areas of jumbled stones across the summit make us wonder if something may have been missed by cartographers.

Photo credit: Janette Kerr - three stone piles, Swae Field

Another refreshment and drawing pause. It’s such a wild wind-swept place; we have to hunker down, level with the heather to hear ourselves speak. From here we look North across the hills to Muckle Roe and, in the distance beyond that, the curved outline of Ronas Hill. To our West lies Sandness Hill, the scattered hillside houses of Fogrigarth to the right of it, and Bridge of Walls to the South. Of course, this is the way we are accustomed to reading the landscape, rather than the way we’ve been learning to read it today.

Susan Pearson - sketchbook drawings

Janette Kerr, watercolour and artgraff painting - view from Swae Field

Photo credit: Steve Poole, From Swae Field

Janette Kerr, plein-air artgraff drawing from Swae Field

Photo credit: Janette Kerr, Swae Field

Photo credit: Jim Sutherland, Swae Field

There’s a slight misting in the air, drops of rain fall on my page, and a rainbow appears, an unscheduled but welcome reminder that hope is our theme for the day. We wonder abstractly what hope may have meant to people in 3000 BC. Did hope play any part in burying the dead? We guess there are certain hopes we all share as humans, whatever the place or century. We all hope for long, healthy and fulfilled lives, a roof over our heads and plenty of food and drink – but even then, wildly differing contexts, lived experience and expectations will surely shape the nature of ‘hope’ in very subjective ways. The temporal chasm between us makes it difficult to imagine what hope might have meant to our tomb builders. How did Neolithic people see rainbows? We can only guess.

(In Norse mythology, a rainbow was seen as the Bifröst bridge, connecting the realm of gods (Asgard) with the realm of humans (Midgard), but then they were more ’sophisticated’ people than our Neolithic crowd).

Photo credit: Susan Pearson, view from Swae Field

At this point there is a parting of the ways as one of our party is losing her boot heel, rather apposite after our walk is about visting heel cairns. Sad to see Vanessa and Susan head off over the hills and back to the road.

The landscape below us is littered with glistening pools of water, the Shetland word for which, Jim tells us, is ‘shuns’ .

Photo credit: Janette Kerr. View from Swae Field

Photo credit: Janette Kerr. Panorama from Swae Field

Jim Sutherland: Plein-air drawing with rainbow from Swae Field

The three of us remaining decide to abandon the original planned search for an unmarked cairn above the Upper Loch of Brouster, and instead make for the Ward of Browland and the imposing chambered cairn we can clearly make out on the skyline. Skirting Skula Water, we climb up to our final destination, an impressive well-preserved heel cairn (HU267515), which now shares the 100m hilltop with an ordnance survey triangulation point.

Photo credit: Janette Kerr. Ward of Browland

Here is a place where boundaries between ancient and modern either clearly and freely coexist or violently clash, depending on your point of view. From one perspective, that trig point, shoved right through the heart of the cairn, displacing the central stones and repurposing them into a rough shelter around it, seems a clear enough case of cultural appropriation. While earlier plundering for treasures was prevented because 19thC cartographers thought the cairn a watch tower rather than a place of burial, the 20thC concrete marker, placed inside the hollowed-out cairn, sits distinct from the time scarred and worn lichen-covered rocks thrown aside and heaped up in its skirts.

Photo credit: Janette Kerr. Panorama from trig point and chambered cairn, Ward of Browland

Out of the wind sheltered by the cairn, we look out from our high vantage point. The sun starts to set, glinting on the distant loch; I can just pick out the Bridge of Walls and the road beyond lost in the haze.

Photo credit: Janette Kerr - from Ward of Brouster

This also being a festival of psychogeography and walking I initiate a conversation about how, as a broad coming together of psychology and place, psycho-geography differs or is similar to emotional geography (and even what that is).

Just the act of walking through a place changes it; just through our presence we alter the land – we follow a sheep’s track, our footprints imbedding in the soft ground, I break off a blade of heather and tuck it onto my sketch book, picking up a stone I place it on top of a cairn. The land we are walking through today has altered since these cairns were first built, just as in 3000 BC the people who built and used them also changed it. A place also changes us – our perceptions challenged, confirmed, shifted.

Steve: There’s an important difference between ‘knowing’ a place through material and numerical methods of measurement and assessment, and ‘knowing’ a place in the sense that it means something to us, stirs memories, or perhaps inspires contentment or unease.

We talk about ‘feeling’ the landscape, how, in phenomenological terms, we engage with it, exist within it and each bring something with us to a place, depending on our own experiences and familiarity with a particular landscape. This is the poetry of place.

Janette Kerr, watercolour - Bridge of Walls from Ward of Browland

Bound by the fading light it’s time to leave. As we walk away, back to the 21st century road, talk slowly turns from consideration of the ancient back to the present, and, incongruously, the discovery of a link between Steve and Jim with Croydon (South East London) and they chat about bands seen, shared knowledge of places and events. I walk on quietly, watching the sheep moving slowly on the hill in front of me, colours in the landscape changing, shadows lengthening. I try to imagine the landscape and Neolithic people living here - without tarmac roads, withouth the houses, without the towering line of telegraph poles that runs past both sites, even sparsely populated as it is. How did they ‘see’ the landscape? The climate was different then, more temperate, perhaps less windy, and less rain than we now experience. Did they farm, what animals did they have? What were their hopes? None of us are archaeologists and we have no clear answers.

Resting my hands on the worn lichen-covered stones, I think about the Neolithic hands that lifted and placed them here, the communities who lived, worked, and died here thousands of years ago. Impossible to know what they were thinking, but perhaps not so different to us. Their hopes were probably not dissimilar to ours, and right now we all need to have hope.

My feet are aching; it’s been a long, but stimulating day.

Janette Kerr

Postscripts - walk thoughts and observations

Susan Pearson:

Immersion in place feels important; there is a deep knowledge that can be achieved by ‘being’ in the landscape -walking and encountering a new place…. or the same places but in an open mindful way…. I feel psychogeography at play as I think about the merging of land, archaeology, geology, geography and art. I’m thinking of land artists, and an exhibition

I visited ‘Dartmoor - Radical landscapes’. The work from there resonates with me; the merging of land, archaeology, geology, geography and art… psychogeography is certainly involved….Specifically an artwork by Alex Hartley (born 1963, based in East Devon, he climbs on Dartmoor); his artwork explores ways of physically experiencing and thinking about our built and natural environments. On Neolithic stones Hartley says, ‘You can reach back through time and touch the very thing that these people touched. It's so rare to find those places. And there's something very specific about Dartmoor, about how iconic the rocky outcrops are. I can see it when I'm away from here and there's not many places that I feel that way about, where they really follow me around and they are in me!’ Hartley 2024.

When I’m walking the hills of Shetland I think about the ways we are physically experiencing the islands. Psychogeography…. works well with my practice and ideas about island-ness. For my next deep dive, I’m off to look on jstor for articles…..

Jim Sutherland:

I’ve made a study of croft houses, outbuildings water mills and crubs. But, apart from appreciating our amazing brochs and the excavations at Jarlshof (which somehow are too manicured to be truly believable) that's possibly why I have usually only managed to reach back three or four hundred years. This Terminalia walk has been a great way to do that by focusing on the 'rumbles o' stanes' recorded as burial cairns. It’s allowed us to focus on questions about our emotional (or psychological) connection with the land, the meaning of the land to us, individual connections and memory.

Walking in Shetland I am drawn to the signs of how we humans have altered the landscape. Modern marks made by man - roads and boundary fences shout very loudly and can drown out the more subtle but significant changes such as ancient boundary walls and burial cairns.

Steve Poole

:

I realise we’ve been led to associate the three cairns we’re visiting today for two 21st century reasons: we happen to live nearby and they happen to have been scheduled as ancient monuments. The third cairn atop the Ward of Browland seems a natural choice for scheduling. It is large, visually impressive and can easily be seen from a distance. But the first two we visited seem rather less obvious. Who deemed them worthy of recognition and why? There are plenty of others to choose from, and many in no worse a state of dilapidation than these two. Scheduling confers value and importance as well as offering a minimal degree of legal protection, but in the present age, not the neolithic. For all we know, when first built, all three were comparably eye-catching. I am suddenly seized by the urge to visit more cairns, confirm them all to be artifacts of timeless value, and shower the council with demands that they too be scheduled.

Emeritus Professor Steve Poole is a social historian focussing on the long 18thC